"A conduit for ideas of the era"- Suzanne Vega

Suzanne Vega reflects on early hits, enduring legacy, and her new album Flying with Angels — a conversation about songwriting, truth-telling, and staying true to your voice.

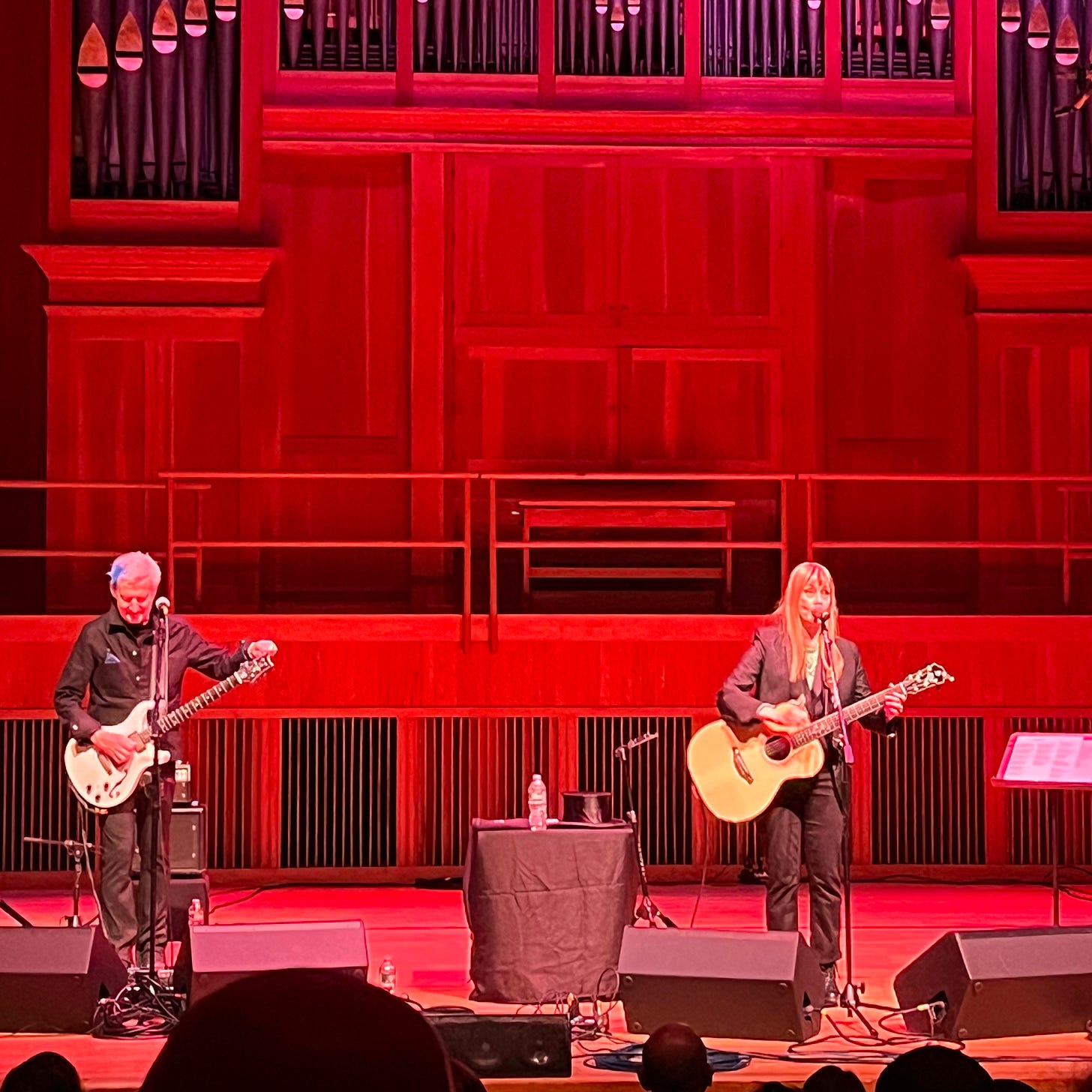

Suzanne Vega is sitting in the morning…in a hotel room outside of Chicago, where she played the night before, and she’s logging onto Zoom. She’s on the road with her longtime musical partner in crime Gerry Leonard, at a moment of transition, a dividing line of her own devising — between retrospection and renewal.

I’ve been listening to Suzanne Vega for most of my life. Her songs — cool, spare, poetic, often deceptively simple — have long been part of the musical fabric for me and many of my generation. From “Luka” and “Tom’s Diner,” to Nine Objects of Desire (still one of my desert island discs), Suzanne has always had the rare ability to observe and evoke without explaining too much. She leaves just enough space in the song for you to project your own story onto hers.

That quality — of clarity without overstatement, of intimacy without confession — has made her work feel timeless. And somehow, even as her songs became global hits, they retained the feeling of having been discovered in secret.

Last September, I saw Suzanne perform in Queens, in a show she called Old Songs, New Songs, and Other Songs. It was part concert, part conversation, a reflection on the arc of a life in music. She told stories, reached back to the beginning, and offered glimpses of what was coming next. That night stayed with me. It felt like a chapter turning. So I asked to talk.

When we spoke recently, her new album Flying with Angels was about to be released — her first record of original songs in almost a decade. What emerged from our conversation was a kind of braided narrative: past and present, clarity and mystery, identity and reinvention.

We talked about her relationship to her early hits, and what it means to carry those songs through the decades. About how “Luka” — a quiet, acoustic song about child abuse — became a mainstream radio success in the late ’80s. About how “Tom’s Diner” evolved from an a cappella experiment to a global club hit, and then, improbably, became the track used to develop the MP3 audio format. (“I’ve somehow been a conduit for ideas of the era,” she told me, with characteristic understatement.)

“Somehow I’ve been a conduit for certain ideas — maybe because of the simplicity of what I did.”

We also talked about what it means to be chosen by a song. Recent world events — especially the war in Ukraine — seemed to call her into service, to bear witness through song. Tracks like “Mariaupol” and “Rats” represent a subtle shift in her approach: less metaphor, more reporting. Not a soapbox, but a snapshot.

And we talked about the writers and artists who shaped her — Lou Reed, Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan — and the ones she’s helped shape in turn. Including her own daughter, Ruby, who appears on the new album and also happens to be a scientist with a PhD in biology. ("She told me at 11 she didn’t want the touring life,” Suzanne said. “And I had to respect that.")

Vega discusses her connection to a vibrant downtown New York songwriting community that included figures like Jack Hardy and Fast Folk magazine, and shares anecdotes from her life on tour, her early performances (including a childhood appearance at Pete Seeger’s feet), and her unexpected intersections with technology and culture.

What struck me most was how consistent she is — not in a fixed or formulaic way, but in her voice, her presence, her way of engaging. Whether she’s performing in Queens, writing about rats in Manhattan, or sitting across a Zoom screen with me, Suzanne Vega is still Suzanne Vega.

And that's no small thing.