Production is saying yes?

Ask 10 producers "what is production" and you will get at least 11 answers.

Earlier this year a video of Rick Rubin being interviewed by Anderson Cooper started circulating. In the clip Rubin, one of the most successful and influential record producers of the moment, claims to have no technical or musical ability. When Cooper asks him what, then, does he get paid to do, Rubin explains “the confidence I have in my taste and my ability to express what I feel has proven helpful for artists.”

If it were coming from someone else, the clip might be easy to dismiss or even ridicule. When it comes to Rubin the results are undeniable. Whatever he’s doing seems to work.

The engineer Ryan Hewitt, who has worked with Rick Rubin for years, described him to me as “a spiritual guru” and “a vibe guy” in our 2017 Third Story podcast interview.

I remember watching the late producer Tommy LiPuma in the studio. He produced some of the most commercially successful jazz records ever made, and much of his magic was, as with Rubin, in the success he brought with him into the room, and in the way he treated the people around him. Something about the respect he paid to the musicians inspired them. His track record inspired them too.

Production is a dark art, something that is often noticed more for its absence or mishandling than it is for its successful execution. Bad production is easier to spot than good production. But what is production? Riffing on that question, I played the role of multiple musicians in a band and their producer in this 2019 video. It’s a parody but a serious one.

For one thing, it’s not always obvious when production begins and when it ends. And anyway, as the saying goes, if you ask ten producers what their job is, you will end up with at least 11 answers.

Third Story podcast conversations with producers like Butch Vig, Daniel Lanois, Andres Levin, Creed Taylor, John Leventhal, Matt Pierson and Larry Klein, among others, have helped to illuminate this.

Growing up, I watched my dad produce records for artists ranging from Mose Allison to Diana Ross. He prioritized having a positive experience in the studio. He didn’t believe that it was necessary to suffer in order to make great work. On the contrary, he believed that if the musicians were enjoying themselves, it would be captured in the music and that tape preserves the joy as well as the notes.

My own approach to production has often consisted of having a hand in every part of the process, from writing and arranging to performing, recording and mixing. There was a time when I believed that I wasn’t really doing anything if I didn’t do everything. But I started to wonder if it might be possible to make a contribution without being so hands-on. Maybe one’s strength could be in having vision, or in supporting the artist, accompanying them on their journey, and facilitating their needs.

I have made an effort to step back and approach each situation with fresh eyes and ears, and to make no assumptions about what the best way is to proceed. Lately my strategy has been to say “yes” as much as possible, even when I don’t necessarily know what that means.

Late last year my dad and I were approached by a well known artist (and friend) to co-produce an album of jazz standards; we said “yes”. We entered with a bit of caution but a lot of enthusiasm. Unlike most of the records I work on, this one looked like it might break out of obscurity. It had a sizable budget, a famous singer, and a big label behind it. But of course when there’s the possibility of success, everyone gets a little more on edge. And there was definitely something a bit edgy about this situation.

We began several months of intense strategizing, planning, budgeting, demoing, transcribing, debating, hiring, firing, and generally psychic drama. Although it was a relatively straightforward assignment, the realities of the project were far from obvious. But for the most part I just kept saying yes. Keep it moving, I thought. Momentum is the name of the game here. And having fun. I felt it was my job to help the artist get what he wanted and I did my best.

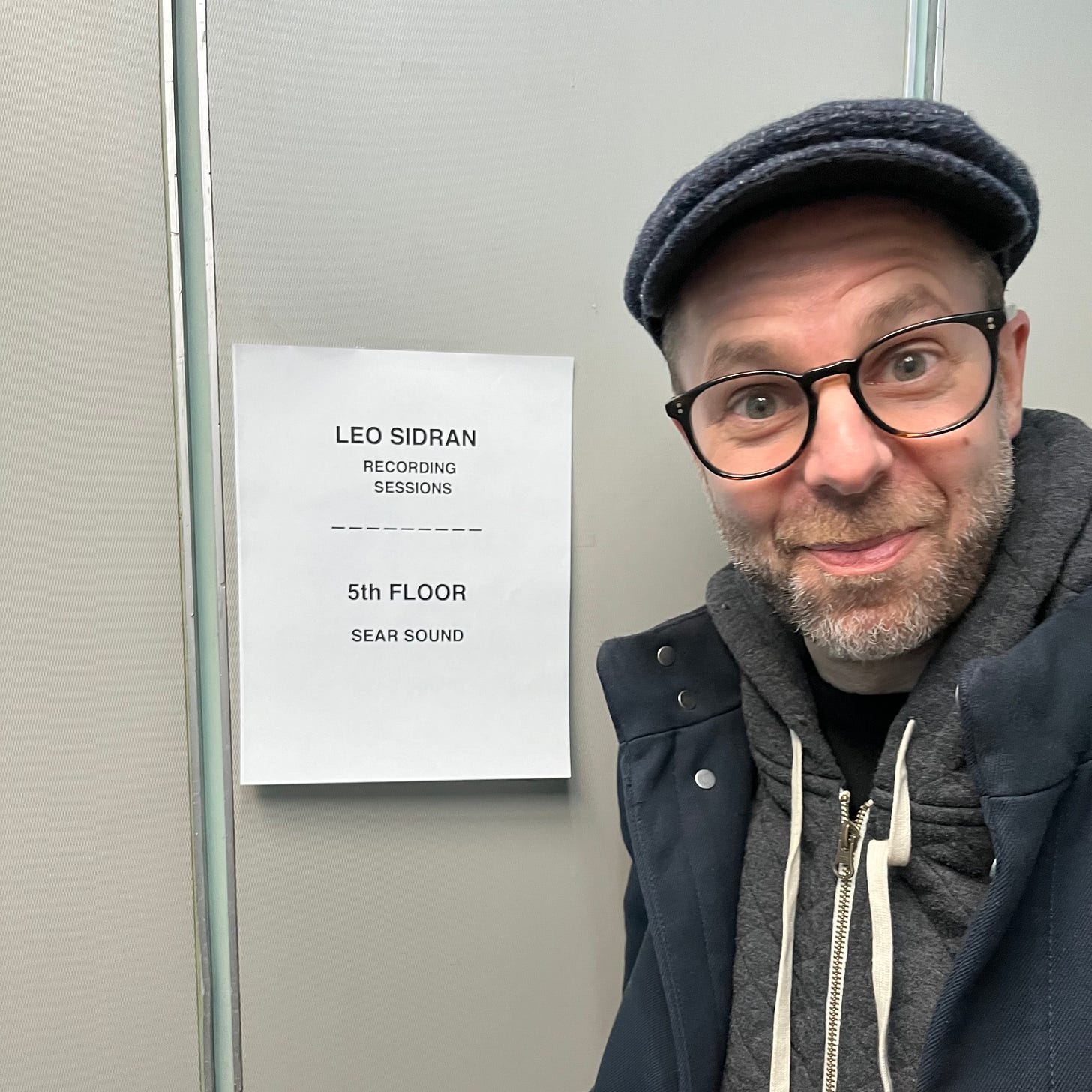

We ended up spending three days in March at Sear Sound in New York with an allstar band that included bassist Larry Grenadier, drummer Herlin Riley, guitarist Bill Frisell and pianist Emmet Cohen, playing a loose collection of standards, recorded by the masterful engineer Chris Allen. For a record of jazz standards, this was a big deal.

It was a joy to luxuriate in the atavistic oasis of Sear Sound, said to be the oldest recording studio in New York, and one of the last great studios to record acoustic music in the city. It was built by the musician, tuba designer, inventor, composer, film producer (many adult films!) and recording engineer Walter Sear.

In March, the days we worked at Sear Sound were easy. We recorded only a few songs each day, ordered lunch from the good sushi place, laughed a lot and told old stories. According to my dad’s law of “if it feels good going to tape, it will feel good listening back”, we were onto something special. I allowed myself to entertain fantasies of future commercial success, bragging rights and Grammy nominations. I imagined telling the story of how I guided the process with positivity and by saying “yes”.

The following week, however, we had a phone meeting with the artist who said he was dissatisfied with the recording and had decided that the sessions we did were unusable. He was saying “no” to my “yes”. There was a cloud, which had been hanging over the project from the beginning, of doubt and second guessing choices. It was difficult to see a way forward but I was still determined to try.

My dad left the project at that moment, but it would be another six weeks of back and forth and additional work before the final nail was in the coffin for me. Then, after nearly six months, it was over. I suspect that nobody will ever hear those recordings.

It was disappointing but not unheard of. Pretty much every producer friend I told about it had a similar story of their own: the record that never came out, the project that got put on pause, the gig they were fired from. It was mildly comforting to know that I was not alone, and that I had joined the tribe of vanquished producers. I wondered if my approach had been misguided. Should I have fought harder for certain things? Should I have focussed less on positivity and been somehow stronger or more forceful? Should I have said “no”?

I wondered when had I started producing the record, and when had I stopped. I wondered if a record is never heard, did it really happen (the proverbial tree falling in the proverbial woods)? And I wondered, what is the difference between a record that comes out and never finds an audience, and one that never has a chance to fail or succeed in the first place.

While I was still licking my wounds, my friend Randy Ingram called me and asked if I would help him with his new piano trio album. The two of us have spent years getting together to talk about the art and craft of making records over too many bottles of natural wine. Ours is a friendship built on a love of listening to and making records.

Randy had most of the pieces in place already; he had hired bassist Drew Gress and drummer Billy Hart, and had reserved a day at Sear Sound. He had booked James Farber, one of the last of his kind of recording engineers, a specialist in capturing jazz performances, to record it. James worked a lot with my dad in the 80s and 90s, he mixed one of my first solo releases and he has been a friend and a mentor to me, as well as another early guest on the Third Story podcast.

Randy is a highly sensitive, melodic and thoughtful composer with very modern sensibilities and a deep understanding and respect for tradition. He had already formulated a lot of his plan. He had developed most of the repertoire and knew what he was going for. He didn’t need a co-producer to do any of the logistical or technical work. He just needed a friend he could trust.

He and bassist Gress already had an easy familiarity with one another. They had even made a duo album together in 2017. It was the inclusion of drummer Billy Hart that made this project unique and exciting for Randy. At 83 years old, Hart is one of the last bridges to a generation of jazz musicians who have become legendary and mythologized.

After he started teaching jazz history classes, Randy had become more aware of lineage and authenticity, especially when it comes to rhythm. He was intimately aware of Billy’s significance in the history of jazz, and more to the point, of his playing style. He likes to say that “Billy has the beat.”

When I first got together with Randy to talk about the record, he played me demos of the songs he wanted to do along with examples of Billy’s playing from other recordings that had informed the writing and song choice. And this wasn’t a trivial thing for him. He recognized a sense of humanity in Billy's beat, and a connection to the lineage of having played with the greats from Jimmy Smith, Shirley Horn and Joao Gilberto, to so many pianists of reference like Herbie Hancock, Richie Beirach, Kenny Kirkland and Fred Hersch.

About a week before the session, Hart realized that he may have inadvertently double booked himself on the recording day and there was a question of whether or not we might have to reschedule. It was a scary and possibly expensive proposition. I asked Randy if he would consider calling another drummer, and I listed a handful names that we both knew would be incredible. But Randy had committed Billy to heart. He said, “I’ve been waiting my whole life to record with Billy.”

Billy had the beat.

“The idea of lineage and authenticity matter to me much more than they used to, especially in a rhythmic sense. Billy Hart has the beat, in the plainest possible terms, and the lineage/authenticity to bring his beat, his colors and intention to any musical situation. To me, there's a depth there with both him and Drew that I aspire to; what it means as a celebration of being and humanity.” - Randy Ingram

Fortunately the schedule ended up working out as planned, and I found myself back at Sear Sound once again in early May for Randy’s record. While the ill fated, big label project from earlier in the year was dogged by second guessing and doubting, Randy’s trio record was an exercise in acceptance and exploration. He was prepared, but he left plenty of room for surprises and for the players to express themselves personally and intuitively.

From time to time Randy would ask a question of me, but for the most part my job seemed to be to say “yes, this is good” which was easy to do because it was good. I was so impressed and moved by Randy’s conception for the project, his commitment to letting it happen, his self awareness, his belief in who he had chosen to surround himself with, and his lack of second guessing. You can feel that sense of comfort and confidence in the music.

Randy Ingram’s album Aries Dance comes out this Friday, October 18 on the Sounderscore label. I am proud to be listed as the co-producer of the record. In this case, it’s because I said “yes”.

If you enjoy Leo Sidran | The Third Story, share it with your friends and earn rewards when they subscribe.

Beautiful story, man.