Remembering Phil Upchurch

A conversation with Ben Sidran about the remarkable career of Phil Upchurch.

The season of fallen soldiers continues. Lately it feels as if every week brings another loss, another name added to the ever-growing roll call of musicians who shaped the soundtrack of our lives. Steve Cropper died just days ago, and the music world has responded as expected—with tributes, memories, and the warm glow of well-earned recognition.

If the mid 20th century was the great blooming of American music and musical innovators, then these early decades of the 21st are the winter that inevitably follows, when even the brightest blooms finally freeze.

But for every musician who gets their flowers, there are countless others who carried the same weight, the same soul, the same history - without standing in the spotlight. Their work is woven into our musical consciousness, even if their names rarely appeared on the marquee.

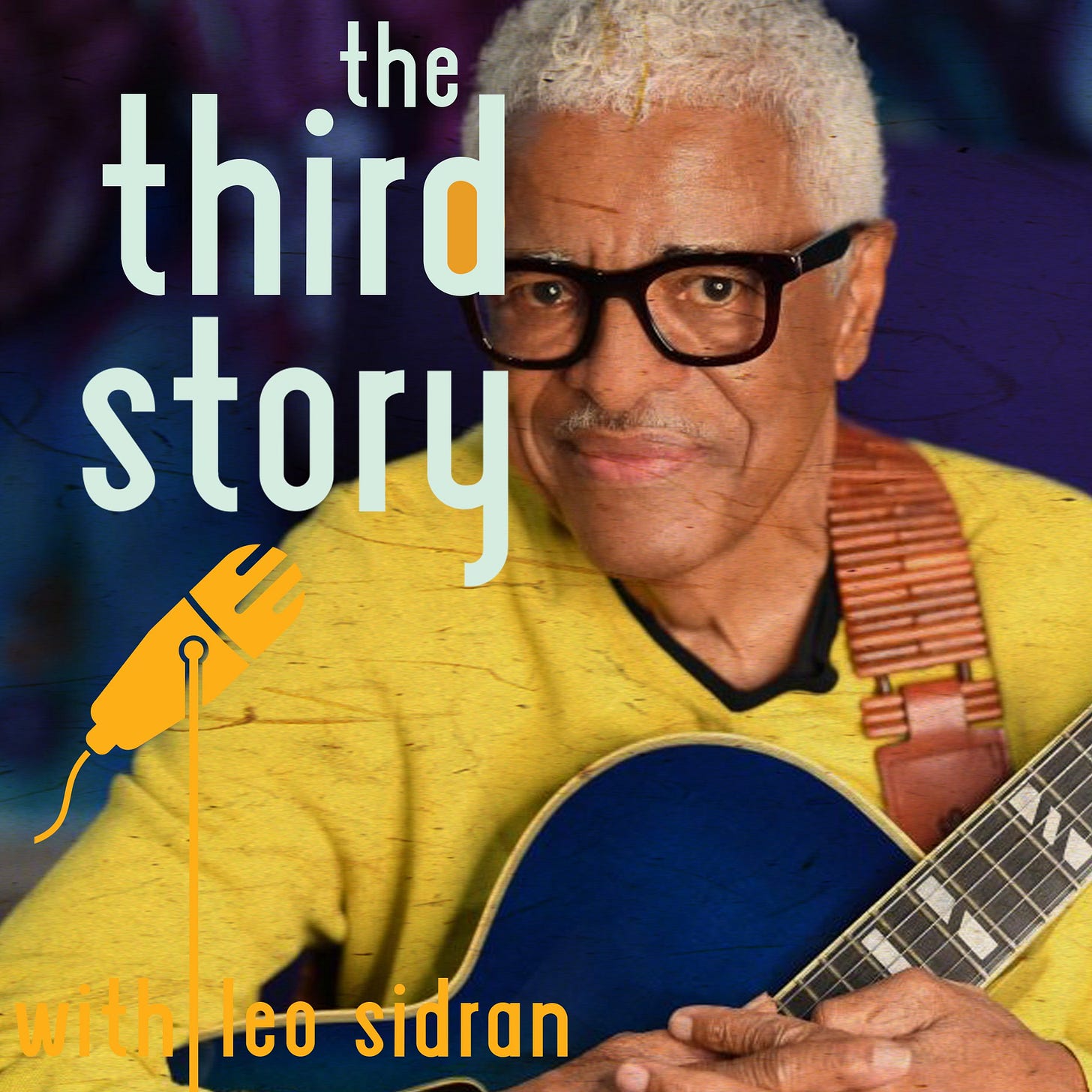

Phil Upchurch was one of those musicians.

Phil Upchurch was a musician’s musician. Those who knew, knew. He played on over a thousand recordings, including some of the most iconic popular music ever made including Michael Jackson’s Off The Wall, Donny Hathaway Live, Chaka Khan’s “I’m Every Woman”, Curtis Mayfield’s Superfly, and George Benson’s Breezin’ to name only a few. He was there in the rooms where the sound of a generation was being created. As my dad, Ben Sidran, tells me in this conversation, “He went from Jimmy Reed to Michael Jackson—that’s pretty unusual.”

What made Phil so remarkable wasn’t just the résumé, impressive as it was. It was his dual identity: a Chicago blues player with the mind of a bebopper. He loved inserting complex harmony into simple forms. He played both guitar and bass with equal authority. He could sit in a studio band and instantly know the right part to play, or step forward and be unmistakably himself.

Producers loved to have him in the studio - Quincy Jones, Tommy LiPuma and Arif Mardin all worked with him repeatedly. He belonged to a generation that didn’t just contribute to the sound of popular music—they invented it. And like so many of the greatest studio players, he was easy to overlook unless you knew exactly where to listen. But if you did listen, you could always hear him. Phil had that rare gift: the ability to be unmistakably himself while serving the larger story.

My relationship with Phil is intertwined with my relationship with my father. They were friends for over fifty years—recording, touring, sharing life.

Some of my earliest memories of being in a studio involve the two of them together, laughing, experimenting, finding the music in the room.

Watch footage of Phil Upchurch recording at Paisley Park for his GoJazz album Whatever Happened To The Blues (produced by my dad). The band includes Michael Bland, Paul Peterson and Ricky Peterson, and if you look closely you’ll even see Ralph Simon hanging in the shadows.

Some of my first gigs as a drummer were with Phil. He treated me with generosity and seriousness, not because I was “Ben’s kid,” but because he could see I was serious about the music and he let me know that there was a place for me, the next set of hands that might carry something forward.

Here we are playing together in 1997 at the Union Theater in Madison, Wisconsin at a concert with Ben Sidran that would later be released as Live at the Celebrity Lounge.

It’s easy to romanticize mentorship, but the truth is it’s how the music survives. It’s how names and sounds persist across time. “We all have a time,” my dad says in the conversation. “Phil lived a full life. And he represented a truth rather than a fiction.”

After Phil’s passing, I did what I’ve done before when a friend left the stage: I called my dad. We talked. We remembered. We tried to fill in the hole left in the fabric. And in doing so, we performed the small sacred act that keeps a musical life alive—we said his name.

Phil Upchurch.

This episode also contains the FIRST EVER appearance by my mother, Judy Sidran, on the Third Story. After nearly a dozen years and hundreds of episodes, I finally figured out how to get Judy on the show, and she shared a small handful of personal recollections of her friendship with Phil too. I am hopeful that this will be the first of many.

Musication, provides in-home music lessons in Brooklyn and Manhattan to children ages 3yrs old and up. Visit www.musication.nyc and mention “The Third Story” to receive two free trial lessons.

You might be interested in a column I wrote about another "musician's musician," also a bass player, who died a few months ago. There really were so few people like this, and likely there will be even fewer, or none, in the future: https://3quarksdaily.com/3quarksdaily/2025/11/danny-thompson-rip.html

Thanks very much for this lovely remembrance. What a legacy. The list of musicians he has influenced would be endless of course. Just a couple of days ago I happened to read of another one: it was the 80th birthday of John Paul Jones, the bassist (and mandolinist and keyboard player and other things) of Led Zeppelin. Someone posted that Jones had first been inspired to take up the bass when he heard You Can't Sit Down.